Many people walk on sidewalks without giving a thought to the surface, but for people with mobility devices such as wheelchairs, scooters and walkers, or people with wheeled devices like strollers or wheeled grocery bags, sidewalks surfaces are incredibly important to the usability and mobility of their community. Far too many communities focus on the aesthetics of sidewalks and disregard the universal design of the surface.

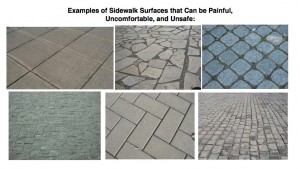

One way to assess the usability of sidewalks is to look at how many lines, or joints, there are on the sidewalk surface. The more joints in a sidewalk the rougher the ride it is for someone with a mobility device. Every line that a person rides over causes a jolt to the body. When one relies on a mobility device to get around their neighbourhood or community these jolts to the system add up over the day, and can cause considerable discomfort or pain. Sidewalks should have as few joints as possible, with minimal deepness of joints, and be made with a flat, non-slip surface.

Another way to assess usability of a sidewalk is to listen to the noise a mobility aid makes while traveling over it. The noisier the ride the harder it is on the body. Imagine a surface of cobblestones which have a lot of joints and do not connect together with a flush fit. You can hear the inaccessibility as a mobility device bounces around on this surface. If, on the other hand, you listen while someone in a mobility aid travels over sidewalks that have continuous, hard, smooth surfaces you will hear very little noise.

Many communities build streetscapes with aesthetics in mind before usability. This can lead to people with mobility aids bypassing the sidewalk and using the road and/or bike lanes. This is not only extremely dangerous but it is also frustrating to cyclists and drivers who need the space and who worry about injuring pedestrians. There are others with mobility devices who are unable to leave their homes because there are no accessible, safe, comfortable sidewalks. They have the means to transport themselves, via their mobility aid, but the sidewalks are not made with them in mind, which isolates them in their own community.

It is sometimes difficult to explain the importance of accessibility issues to those who have not had first-hand experience but in this case there is a parallel many people without mobility devices will have experienced, which explains why properly made, nod-decorative, and safe sidewalks are necessary. Think of rumble strips. How many of us have been in a vehicle on a highway when the car veers off the main path of travel and onto the rumble strips? These strips cause a quick jolt which grabs the attention of the driver to remind them to get back on course. The jolt that the driver experiences from the rumble strips is very similar to the jolts that people with mobility devices experience on sidewalks. Two big differences being that those with mobility aids are expected to continue to drive on these rumble strips (or sidewalk surfaces) and that they often have bodies more susceptible to pain and/or discomfort. Ask yourself, would you want to drive on rumble strips all the time? Especially if you have issues with pain? The fact is that people with mobility aids are expected to travel over surfaces similar to rumble strips in communities across our province, and it is an expectation that needs to stop.

While decorative surfaces can add to the aesthetic appeal of a community they make the streetscapes less universally accessible. There are, however, ways of incorporating decorative bricks and paving stones without causing accessibility concerns. One way is to place them off the main path of travel. Paving stones and bricks can be used as decoration on the border of the path of travel, which not only adds to the attractiveness of the sidewalk but it also adds to the safety as it creates a buffer zone between the pedestrian and the roadway, and it acts as wayfinding, indicating to people with visual impairments the location of the path of travel.

It is vitally important to create communities where the environment does not disable the person’s ability to participate in their community. Sidewalks are one of the most important parts of universally accessible streetscapes. In addition to mobility devices and strollers it is also important for people with visual impairments, agility issues, and small children. Having a stable, solid, flat, non-slip surface makes the community more open, inviting, and pain-free. With a growing number of older adults and the booming mobility aid market we must make streets that are usable, comfortable, safe and as painless as possible for all types of pedestrians. We must ensure their safety by keeping pedestrians on the sidewalk and off the roads. And we must ensure that those who have transportation, by way of mobility devices, can use them, and not become cut off to the outside world due to a lack of accessible sidewalk surfaces.